Design of ProtoMS¶

ProtoMS is a powerful simulation program that is capable of being used in many different ways. ProtoMS was originally designed to perform Monte Carlo free energy calculations on protein-ligand systems, so a lot of the terminology and ideas associated with ProtoMS derive from protein-ligand Monte Carlo methodology. While the code was originally designed with this use in mind, the framework is sufficiently flexible to allow the study of a wide range of different systems, using a wide range of simulation methodology.

At the core of ProtoMS are four central concepts;

- Proteins/Solutes/Solvents/GCSolutes ProtoMS divides all molecules to be simulated into ‘proteins’, ‘solutes’ and ‘solvent’.

- Classical Forcefields ProtoMS Uses a generic classical forcefield to calculate the energy of the molecules. This forcefield may be specialised such that ProtoMS is able to implement a wide range of modern molecular mechanics forcefields.

- Perturbations ProtoMS provides support for free energy calculations by allowing forcefields and geometries to be perturbed using a

coordinate. The forcefield for any protein, solute or solvent may be perturbed, and the geometry of any solute may be perturbed.

coordinate. The forcefield for any protein, solute or solvent may be perturbed, and the geometry of any solute may be perturbed. - Generic Moves ProtoMS is designed around the concept a ‘move’. The move can do anything, from a Monte Carlo translation of solvent to a docking type move on a solute. A simulation is constructed by stringing a collection of moves together.

Proteins / Solutes / Solvents / GCSolutes¶

ProtoMS divides all of the molecules loaded within a system into solvents, GCsolutes, solutes and proteins

- solvents A solvent is any rigid molecule. Solvents may only be translated and rotated, and by default, 75000 solvent molecules may be loaded, each consisting of up to 10 atoms. Solvent molecules do not have to be small - a rigid lipid molecule could be modelled as a solvent. There is no requirement for the solvents loaded in a system to be the same. Indeed every solvent loaded could be a different type of molecule!

- GCsolutes Like a solvent molecule, GCsolutes are rigid. They have the same properties as previously described for solvents, except GCsolutes are restrained to a defined region in the simulation.

- solutes A solute is any flexible molecule. Solutes can be translated and rotated, and change their internal geometry. By default 60 solutes, each composed of 10 residues, each composed of 100 atoms may be loaded simultaneously. Solute molecules are described using z-matrices, thus a solute molecule is perhaps what you would be most familiar with from other Monte Carlo simulation programs. Note that you can describe a protein molecule as a solute, and that you do not need to load it up as a ‘protein’.

- proteins A protein is any flexible chain molecule (polymer). A protein is composed of a linear chain of residues, with interresidue bonds connecting one residue to the next. By default, ProtoMS can load up to 3 proteins simultaneously, each protein consisting of 1000 residues, each consisting of up to 34 atoms.

Solvents

Solvents are loaded into ProtoMS from PDB files (see section Solvent File). Each solvent molecule is identified by its residue name (the fourth column in the PDB file), e.g. ProtoMS identifies the TIP4P solvent with the residue name ‘T4P’. ProtoMS loads the coordinates of the solvent from the PDB file, and then assigns the parameters for the solvent from a solvent template (see section Templates). The solvent template contains the information necessary to identify all of the atoms in the solvent molecule and to assign forcefield parameters to each atom. Note that this version of ProtoMS uses the coordinates of the solvent molecule that are present in the PDB file. ProtoMS does not yet have the capability to modify these coordinates to ensure that the internal geometry of the solvent is correct for the solvent model. This means that as solvents are only translated and rotated, the internal geometry of the solvent molecule loaded at the start of the simulation will be identical to that at the end of the simulation.

GCSolutes

Like solvents, GCsolutes are loaded into ProtoMS from PDB files (see section GCsolute File). Each GCsolute molecule is identified by its residue name (the fourth column in the PDB file). ProtoMS loads the coordinates of the GCsolute from the PDB file, and then assigns the parameters for the GCsolute from a GCsolute template (see section Templates). This template contains the information necessary to identify all of the atoms in the solvent molecule and to assign forcefield parameters to each atom. Alongside translational and rotational moves, the intermolecular energy between the GCsolute and the system can be sampled.

Solutes

Solutes are also loaded into ProtoMS from PDB files (see section Solute File). Each solute molecule is identified by its solute name, which is given in the HEADER record of the PDB file. ProtoMS obtains the coordinates of the solute from the PDB file, and will then find a solute template that matches this solute name (see Templates). The solute template is used to build the z-matrix for the solute, and to assign all of the forcefield parameters. The solute template is also used to assign the connectivity of the solute and to define the flexible internal coordinates. The solute molecule is constructed using the z-matrix, with the reference being three automatically added dummy atoms, called ‘DM1’, ‘DM2’ and ‘DM3’, all part of residue ‘DUM’. These dummy atoms are automatically added by ProtoMS at the geometric center of the solute, as a right angled set of atoms pointing along the major and minor axes of the solute.

Proteins Proteins are loaded into ProtoMS via PDB files (see section Protein File). Each PDB file may only contain a single protein chain. ProtoMS constructs the linear chain of molecules based on the order of residues that it reads from the PDB file, and will ignore the residue number read from the PDB file. This means that you must ensure that you have the residues ordered correctly within the PDB file. ProtoMS assigns to each residue both a chain template (see section Templates), that describes the backbone of the residue, and a residue template (see section Templates), that describes the sidechain. The residue template is located based on the name of the residue given in the fourth column in the PDB file (e.g. ‘ASP’ or ‘HIS’). The chain template is located based on the chain template associated with the residue template for the position of the residue within the chain. For example, residue ‘ASP’ has a standard amino acid backbone chain template if this residue was in the middle of the chain, an NH+ capped backbone chain template 3 if this was the first residue of the chain (and thus at the n-terminus), and a CO– capped backbone chain template 2 if this were the last residue of the chain (and thus at the c-terminus). If the protein consisted of only one residue, then the zwitterionic amino acid chain template would be used for ‘ASP’.

ProtoMS obtains the coordinates of each residue from the PDB file, and will then use the residue and chain templates to build the z-matrix for each residue, and to assign all of the forcefield parameters.

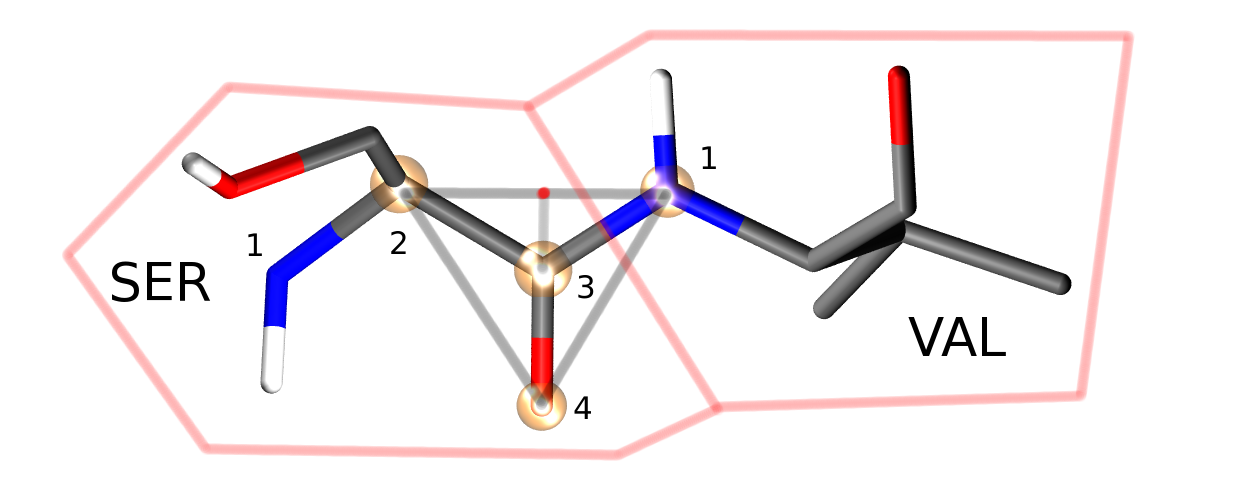

Proteins are moved in a different manner in ProtoMS compared to other Monte Carlo packages that are available. Each residue is moved independently, using both the internal geometry moves defined by the template z-matrix, and by backbone translation and rotation moves of the chain atoms (see figure above).

Four atoms from each protein residue are designated as backbone atoms (bbatoms). For most residues these atoms are the N, CA, C and O atoms respectively. The four backbone atoms for two neighbouring residues are shown above. The protein backbone move moves the last three bbatoms of one residue and the first bbatom of the next residue. This is because the moves assumes that these four bbatoms form a rigid triangle (as is shown by the grey lines). The four atoms are translated and rotated as a rigid triangle, with the origin of rotation of the triangle centered on the intersection of the vector between bbatoms 2 and 1, and the vector between bbatoms 3 and 4 (marked as a red dot directly above the C=O bond). Because this triangle is translated and rotated as a rigid unit, all atoms connected to the atoms of this triangle will also be translated and rotated as a rigid unit.

Four special backbone atoms (bbatoms) are identified in the chain-backbone of each residue. These atoms form the reference from which the rest of the residue atoms are built. These four atoms can be translated and rotated as a rigid unit via protein backbone moves (see figure above). As the rest of the residue is constructed from these bbatoms, the rest of the residue is thus also translated and rotated. Because the bbatoms are translated and rotated as a rigid unit, the internal geometry of these backbone atoms are held constant throughout the simulation. This means that the internal geometry of the bbatoms is taken from the PDB file, and may not be modified by the chain or residue templates. It is also not possible to build missing bbatoms, so they must all be present in the PDB file.

Once the coordinates and z-matrices of each residue have been assigned, interresidue bonds are added between the first bbatom of each residue and the third bbatom of the previous residue (e.g. for ‘ASP’, bonds would be added from the ‘N’ atom of the ‘ASP’ residue to the ‘C’ atom of the preceeding amino acid residue). If the length of this bond is less than 4 A then this bond is added as a real bond, and its energy is evaluated as part of the forcefield. However, if the length is greater than 4 A, then this bond will be added as a dummy bond, and a warning message output. This is useful in cases where you wish to load up a protein scoop, e.g. from around the active site. This option should be used with care in conjunction with backbone moves.

| Parameter | Description | Values |

|---|---|---|

| MAXPROTEINS | Maximum number of proteins | 3 |

| MAXRESIDUES | Maximum number of residues per protein | 1000 |

| MAXSCATOMS | Maximum number of atoms per protein residue | 30 |

| MAXSOLUTES | Maximum number of solutes | 60 |

| MAXSOLUTERESIDUES | Maximum number of residues per solute | 10 |

| MAXSOLUTEATOMSPERRESIDUE | Maximum number of solute atoms per residue | 100 |

| MAXSOLVENTS | Maximum number of solvent molecules | 75000 |

| MAXSOLVENTS | Maximum number of GCsolute molecules | 75000 |

| MAXSOLVENTATOMS | Maximum number of atoms per solvent | 10 |

Limits

ProtoMS is written using slightly extended Fortran 77 (see Programming Language). This means that the maximum numbers of loaded proteins, solutes and solvents has to be set at compile time. Table 1.0 gives the default values for the maximum number of proteins, solutes and solvents. Please note that you may change these numbers to fit the system that you are interested in, e.g. if you were investigating a single protein in a lipid bilayer then you may choose to model the lipid as a solute (thus requiring a large increase in the number of solute molecules, but a decrease in the number of solute residues), and you could reduce the maximum number of protein molecules to one. By balancing the numbers of protein, solutes and solvents you should find that you are able to load up the system that you want to simulate.

Classical forcefields¶

ProtoMS was designed to perform simulations using a range of different molecular mechanics (MM) forcefields. To achieve this aim, a generic forcefield has been implemented, and this can be specialised into a specific, traditional forcefield. Specifically, ProtoMS supports the use of the Amber ff99, ff99SB and ff14SB protein forcefields, along with OPLS 96. The General Amber Forcefield (GAFF) is used for solutes, whilst various solvent forcefield models including TIP3P, TIP4P, SPC and SPC/E can be used.

The forcefield in ProtoMS is comprised of several terms;

Intermolecular Potential

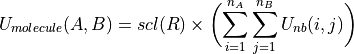

An intermolecular potential acts between all molecules within the system. The intermolecular potential between a pair of molecules, A and B,  , with A consisting of

, with A consisting of  atoms and B consisting of

atoms and B consisting of  atoms, is formed as the sum of the non-bonded potential,

atoms, is formed as the sum of the non-bonded potential,  between each pair of atom sites, i and j, between the two molecules, scaled by a constant, scl, e.g.

between each pair of atom sites, i and j, between the two molecules, scaled by a constant, scl, e.g.

(1)

where R is the shortest distance between a pair of atom sites between the molecules. The scaling factor is set according to

where  and

and  are the non-bonded cutoff and feather parameters.

are the non-bonded cutoff and feather parameters.

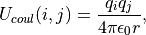

The non-bonded potential between the pair of atoms is evaluated as the sum of the Coulombic and Lennard-Jones (LJ) potentials between the atoms,

(2)![U_{nb}(i,j) = \frac{q_i q_j}{4\pi\epsilon_{0} r(i,j)} + 4\epsilon_{ij}\biggl[ \biggl(\frac{\sigma_{ij}}{r(i,j)}\biggr)^{12} - \biggl(\frac{\sigma_{ij}}{r(i,j)}\biggr)^6 \biggr],](_images/math/ecc69aa9f57db7f0840212102c422887f81df344.png)

where  and

and  are the partial charges on the two atom sites, r(i, j) is the distance between the atom sites,

are the partial charges on the two atom sites, r(i, j) is the distance between the atom sites,  is the permittivity of free space and

is the permittivity of free space and  and

and  are the Lennard Jones parameters for the atom site pair i and j. The LJ parameters for an atom site pair are calculated as the average of the LJ parameters for the same site pair.

are the Lennard Jones parameters for the atom site pair i and j. The LJ parameters for an atom site pair are calculated as the average of the LJ parameters for the same site pair.

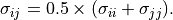

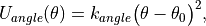

Either the arithmetic average is used, or the geometric average is used, e.g.

(3)

(4)

The AMBER family of forcefields use the arithmetic average for  , and the geometric average for

, and the geometric average for  , while the OPLS family of forcefields use the geometric average for both parameters. The intermolecular potential is formed as the sum of the non-bonded potential over all pairs of atom sites. It should be noted that an atom site does not necessarily need to lie at the center of each atom, and it may lie between atoms, or at the location of any lone pairs. Individual atoms may possess many atom sites, or even no atom sites.

, while the OPLS family of forcefields use the geometric average for both parameters. The intermolecular potential is formed as the sum of the non-bonded potential over all pairs of atom sites. It should be noted that an atom site does not necessarily need to lie at the center of each atom, and it may lie between atoms, or at the location of any lone pairs. Individual atoms may possess many atom sites, or even no atom sites.

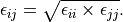

Bond Potential

A bond potential acts over all of the explicitly added, non-dummy bonds within a molecule. ProtoMS makes no attempt to find any implicit bonds within a molecule, and it is not possible to add a bond between atoms of different molecules. The energy of each bond,  , is evaluated according to

, is evaluated according to

(5)

where r is the bond length,  is the force constant for the bond, and

is the force constant for the bond, and  is the equilibrium bond length. The total bond energy of a molecule is the sum of the bond energies for all of the bonds within the molecule, and the total bond energy of the system is the sum of the bond energies for each of the molecules in the system.

is the equilibrium bond length. The total bond energy of a molecule is the sum of the bond energies for all of the bonds within the molecule, and the total bond energy of the system is the sum of the bond energies for each of the molecules in the system.

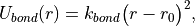

Angle Potential

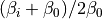

An angle potential acts over all angles between atoms that are connected by non-dummy bonds, and over all non-dummy angles that have been explicitly added to the molecule. The energy of each angle, Uangle , is evaluated according to

(6)

where  is the size of the angle,

is the size of the angle,  is the force constant for the angle, and

is the force constant for the angle, and  is the equilibrium angle size. The total angle energy of a molecule is the sum of the angle energies for each of the angles within the molecule, and the total energy of the system is the sum of the angle energies for each of the molecules in the system.

is the equilibrium angle size. The total angle energy of a molecule is the sum of the angle energies for each of the angles within the molecule, and the total energy of the system is the sum of the angle energies for each of the molecules in the system.

Urey-Bradley Potential

A Urey-Bradley potential may act between the first and third atoms of some of the angles that are evaluated for the angle potential. If this is the case, then a Urey-Bradley energy is added onto the angle energy. The Urey-Bradley energy,  , is evaluated according to

, is evaluated according to

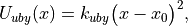

(7)

where x is the distance between the first and third atoms,  is the Urey-Bradley force constant, and

is the Urey-Bradley force constant, and  is the equilibrium distance.

is the equilibrium distance.

Dihedral Potential

A dihedral potential acts over all dihedrals between atoms that are connected by non-dummy bonds, and over all non-dummy dihedrals that have been explicitly added to the molecule. Such explicitly added dihedrals may be used to add improper dihedrals that maintain the stereochemistry of chiral centers. The energy for each dihedral,  , is formed as the sum of n cosine terms,

, is formed as the sum of n cosine terms,

(8)![U_{dihedral}(\phi) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} k_{i1}\bigl[1.0 + k_{i2}\bigl(cos(k_{i3}\phi + k_{i4})\bigr)\bigr],](_images/math/216d87dbdc21e46e542b4ea16247b6edeb7bcfa0.png)

where  to

to  are dihedral parameters and

are dihedral parameters and  is the size of the dihedral. The total dihedral energy of a molecule is the sum of the dihedral energies for each of the dihedrals in the molecule, and the total dihedral energy of the system is the sum of the dihedral energies of each of the molecules.

is the size of the dihedral. The total dihedral energy of a molecule is the sum of the dihedral energies for each of the dihedrals in the molecule, and the total dihedral energy of the system is the sum of the dihedral energies of each of the molecules.

Intramolecular non-bonded Potential

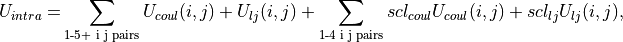

An intramolecular non-bonded potential acts between all intramolecular pairs of atoms that are either not connected by a non-dummy bond, or are not both connected to a third atom by a non-dummy bond. To make this more clear, if two atoms are connected by a non-dummy bond then they are said to be 1-2 bonded. If two atoms are both connected to a third atom by non-dummy bonds, then they are said to 1-?-3, or 1-3 bonded. Similarly, if the pair of atoms are connected together via two atoms via non-dummy bonds, then they are said to be 1-?-?-4, or 1-4 bonded. An intramolecular non-bonded potential does not act over 1-2 or 1-3 bonded pairs within a molecule, but does act over 1-4 bonded pairs and above. Note that ProtoMS only looks at the non-dummy bonds between atoms, and will not consider whether or not there are non-dummy angles, Urey-Bradley or dihedral terms involving these atoms.

The intramolecular non-bonded potential of a molecule,  is the sum of the non-bonded energy between all 1-5 and above pairs of atoms within the molecule, plus the sum of the non-bonded energy between all 1-4 atoms scaled by a 1-4 scaling factor, e.g.

is the sum of the non-bonded energy between all 1-5 and above pairs of atoms within the molecule, plus the sum of the non-bonded energy between all 1-4 atoms scaled by a 1-4 scaling factor, e.g.

(9)

where

(10)

and

(11)![U_{lj}(i,j) = 4\epsilon_{ij}\biggl[ \biggl(\frac{\sigma_{ij}}{r}\biggr)^{12} - \biggl(\frac{\sigma_{ij}}{r}\biggr)^6 \biggr].](_images/math/800cdc2e0331d54277b8d2e2ae5cb1cd7592adf3.png)

Equations (10) and (11) are the Coulomb and Lennard Jones equations, as seen in the intermolecular potential in equations (1) and (2).  and

and  are the Coulomb and Lennard Jones scaling factors.

are the Coulomb and Lennard Jones scaling factors.

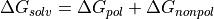

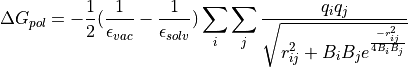

Generalized Born Surface Area potential

While free energy simulations are usually conducted in explicit solvent, ProtoMS supports Generalized Born Surface Area (GBSA) implicit solvent models. Relatively few free energy implicit solvent studies have been conducted and such option should be tested carefully before embarking onto expensive free energy simulations. The GBSA theory assumes that the total solvation free energy of a molecule A is a sum of a polar and non-polar energy term:

(12)

The second term, is simply proportional to the solvent accessible surface area (SASA) of the molecule, times a parameter that depends on the atom types present in the molecule. The first term is more complex and derived from the following equation :

(13)

and

and  are the dielectric constants of the vacuum and the solvent respectively,

are the dielectric constants of the vacuum and the solvent respectively,  the atomic partial charge of atom i,

the atomic partial charge of atom i,  the distance between a pair of atoms ij, and

the distance between a pair of atoms ij, and  is the effective Born radius of atom i.

is the effective Born radius of atom i.

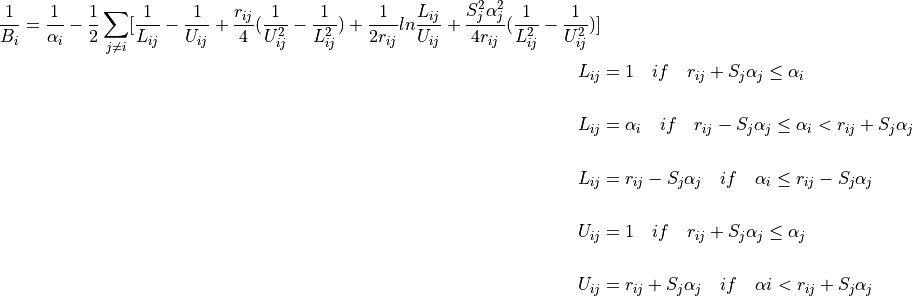

The effective Born Radius  is in essence the spherically averaged distance of the solute atom to the solvent. An accurate estimate of this quantity is essential to calculate high quality solvation free energies. It is however fairly complex to compute as it formalyl involves an integral over the position of all the atoms in the system. While numerical techniques can calculate such value, they are too slow to be of practical use in a simulation. In ProtoMS, the effective Born radii are calculated using the Pairwise Descreening Approximation (PDA) method.

is in essence the spherically averaged distance of the solute atom to the solvent. An accurate estimate of this quantity is essential to calculate high quality solvation free energies. It is however fairly complex to compute as it formalyl involves an integral over the position of all the atoms in the system. While numerical techniques can calculate such value, they are too slow to be of practical use in a simulation. In ProtoMS, the effective Born radii are calculated using the Pairwise Descreening Approximation (PDA) method.

where  is the distance between a pair of atoms ij and

is the distance between a pair of atoms ij and  is the intrinsic Born radius of atom i, that is, the Born radius that atom i would adopt if it was completely isolated. Finally

is the intrinsic Born radius of atom i, that is, the Born radius that atom i would adopt if it was completely isolated. Finally  is a scaling factor which compensates for systematic errors introduced by this approximate Born radii calculation.

is a scaling factor which compensates for systematic errors introduced by this approximate Born radii calculation.

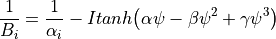

As the name says, the technique approximate the descreening (the extent to which a nearby atom j displaces a volume that would have otherwise been occupied by solvent) by a fast summation of pairwise terms. It is however not rigorous and has to be parameterised carefully to yield robust performance. The PDA method tend to systematically underestimate the Born radius of buried atoms because it incorrectly assign high dielectric constants to numerous small voids and crevices that exist between atoms in a protein and are not occupied by water. To increase accuracy, a re-scaling technique has been implemented.

where I is the summation term from the PDA calculation,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are parameters taken from the literature.

are parameters taken from the literature.

The rescaling option has not been used extensively in ProtoMS and should be used with caution. It appears it may prove useful when simulation buried protein binding sites.

The GBSA force field implemented in ProtoMS was parameterised to be used with the AMBER99 and the GAFF force fields. While alternative force fields could be used, a loss of accuracy could be expected.

GBSA simulations are order of magnitude more efficient than explicit solvent simulations of small isolated molecules. However, they slow down rapidly when the size of the system increases. This is especially notable in Monte Carlo simulations where a small movement of part of a system formally warrants the computation the entire solvation energy of the system. This issue arises because the GBSA energy terms are not strictly pairwise decomposable. It is possible to use however different techniques to increase the speed of a GBSA simulation. Cutoffs in the calculation of the Born radii are introduced and in addition the update of pairwise GB energies can be skipped if the Born radii of either atoms have not changed more than a certain threshold value after a MC move. Because this option will introduce energy drifts, it is advised to periodically recalculate rigorously the GB energy. In addition, a more complex Monte Carlo move is implemented in ProtoMS. This option allows to conduct a simulation with a crude GBSA model and a low cutoff for the non bonded energy terms. Normally the predicted macroscopic properties would suffer from such crude treatment of intermolecular energies. However, periodically, a special acceptance test is employed to remove the bias introduced by the crude potential and ensure that the equilibrium density of states generated by the Monte Carlo simulation converges to the equilibrium density of states suitable for the standard biomolecular potential.

Actual speedups using either techniques are system dependent and optimisation of the different parameters can be a complex task. It is advised to use the default parameters described latter in the manual.

Caveats

ProtoMS implements this forcefield mostly as described. However there are a few shortcuts that are taken to improve the efficiency of the code. These shortcuts are based on the three-way split of the molecules of the system into solvents, solutes and proteins

- solvents As solvents are rigid, there is no need to evaluate any of the intramolecular potentials. ProtoMS thus only evaluates the intermolecular energy of solvent molecules.

- solutes ProtoMS evaluates the forcefield of solute molecules exactly as described, with no shortcuts.

- proteins. ProtoMS implements a protein as a chain of residues. As these molecules can be large, and typically larger than the non-bonded cutoff, ProtoMS implements the non-bonded cutoff differently for proteins. Instead of evaluating the non-bonded cutoff for the protein as a whole, ProtoMS implements a residue-based cutoff, with the cutoff scaling factors evaluated individually for each residue. Additionally, the intramolecular non-bonded energy is also scaled according to the non-bonded cutoffs given in equation (1). If you do not want to use residue based cutoffs, then it is possible to tell ProtoMS to use a molecule based cutoff, in which case the forcefield for proteins will be evaluated exactly as described with no shortcuts.

Perturbations¶

ProtoMS is capable of calculating the relative free energy of two systems. ProtoMS does this by perturbing one system into the other through the use of a  -coordinate. If A and B are the two systems of interest, then the forcefield is constructed such that at

-coordinate. If A and B are the two systems of interest, then the forcefield is constructed such that at  = 0.0 the forcefield represents system A, at

= 0.0 the forcefield represents system A, at  = 1.0 the forcefield represents system B, and at

= 1.0 the forcefield represents system B, and at  value inbetween, the forcefield represents a hybrid of A and B.

value inbetween, the forcefield represents a hybrid of A and B.

ProtoMS implements two methods of perturbing between systems A and B;

- Single topology System A is perturbed into system B by scaling the forcefield parameters such that the model morphs from A to B.

- Dual topology System A and B are simulated together, with

scaling the total energies of A and B such that one system is turned off as the other is turned on.

scaling the total energies of A and B such that one system is turned off as the other is turned on.

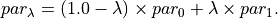

Single Topology Calculations

ProtoMS assigns two sets of parameters to every single forcefield term; one parameter represents that term at  (

( ), the other represents that term at

), the other represents that term at  (

( ).

).  is used to linearly scale between these two parameters to obtain the value of the parameter at each value of

is used to linearly scale between these two parameters to obtain the value of the parameter at each value of  (

( )

)

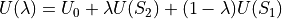

(14)

This equation is used to scale the charge,  and

and  parameters assigned to each atom site (see equations (1)), and the force constants (

parameters assigned to each atom site (see equations (1)), and the force constants ( ,

,  and

and  ) and equilibrium sizes (

) and equilibrium sizes ( ,

,  and

and  ) for the bond, angle and Urey-Bradley terms (see equations (5), (6) and (7)). This equation is not used to scale the dihedral parameters, as the functional form of the dihedral potential is more complicated. Rather than scale the dihedral parameters, ProtoMS uses

) for the bond, angle and Urey-Bradley terms (see equations (5), (6) and (7)). This equation is not used to scale the dihedral parameters, as the functional form of the dihedral potential is more complicated. Rather than scale the dihedral parameters, ProtoMS uses  to scale the total energy of each dihedral;

to scale the total energy of each dihedral;

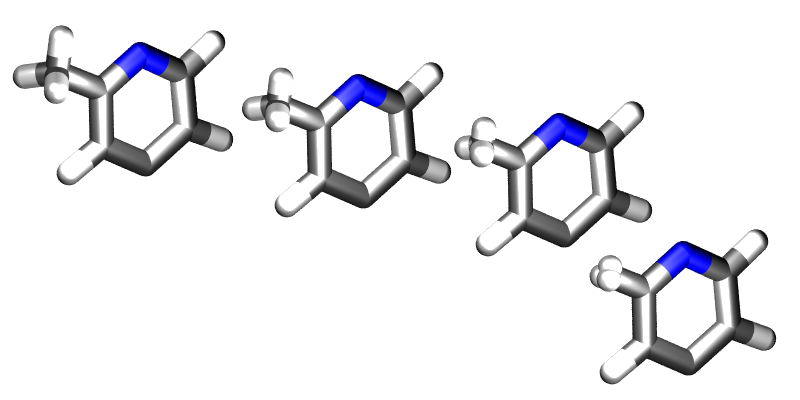

(15)

where  is the dihedral energy using the parameters for

is the dihedral energy using the parameters for  ,

,  is the dihedral energy using the parameters for

is the dihedral energy using the parameters for  , and

, and  is the scaled dihedral energy at that value of

is the scaled dihedral energy at that value of  .

.

Any and all parts of the forcefield can be scaled. This includes all of the forcefield parameters of any solutes, all of the parameters of any proteins, and all parameters of any solvent molecules. While this is very useful, and enables perturbations of any and all parts of the system, there are many cases where just changing the forcefield parameters is not sufficient to smoothly morph from one system into the other. There are many cases where the geometry of the molecules needs to be changed with  . Fortunately ProtoMS provides this capability for solute molecules. Any internal coordinates that are part of the z-matrix of a solute molecule may perturbed with

. Fortunately ProtoMS provides this capability for solute molecules. Any internal coordinates that are part of the z-matrix of a solute molecule may perturbed with  . Geometry variations are a powerful tool as they allow for very complicated, yet very smooth transitions between two systems to be described. A good example of such a transition is the annihilation of the hydrogen atoms as a methyl group is morphed into a single hydrogen.

. Geometry variations are a powerful tool as they allow for very complicated, yet very smooth transitions between two systems to be described. A good example of such a transition is the annihilation of the hydrogen atoms as a methyl group is morphed into a single hydrogen.

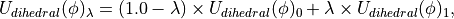

Geometry variations allow for a smoother transition between two systems, for example here a methyl group is smoothly converted into a hydrogen.

As well as enabling smooth transitions between systems, geometry variations may be used to calculate potentials of mean force along structural coordinates.

Dual Topology Calculations

A dual topology method to calculate free energy changes is also available in ProtoMS. In the single topology method force field terms were linearly interpolated so that they match the force field parameters suitable for particular molecule at either end of the perturbation ( 0.0 or

0.0 or  1.0). As two molecules often differ not only in their force field terms but also their geometry, it is often necessary to modify the internal coordinates as well. This is relatively easy In simple cases (morphing a methyl group into a hydrogen group) but for larger, complex, perturbations this is often cumbersome if not impossible. In the dual topology method no geometry variations are attempted. However, the interaction energy of a pair of solutes with their surroundings (solvent, protein, other solutes), is gradually turned on or off with the coupling parameter.

1.0). As two molecules often differ not only in their force field terms but also their geometry, it is often necessary to modify the internal coordinates as well. This is relatively easy In simple cases (morphing a methyl group into a hydrogen group) but for larger, complex, perturbations this is often cumbersome if not impossible. In the dual topology method no geometry variations are attempted. However, the interaction energy of a pair of solutes with their surroundings (solvent, protein, other solutes), is gradually turned on or off with the coupling parameter.

(16)

Equation (16) thus shows that at any given value of  , the total energy of the system consists in a term

, the total energy of the system consists in a term  that is independent of the perturbation and a term

that is independent of the perturbation and a term  and

and  which is a function of the intermolecular energies of the pair of solutes for which a free energy change is to be calculated.

which is a function of the intermolecular energies of the pair of solutes for which a free energy change is to be calculated.

A dual topology setup is simpler and more generally applicable than a single topology setup. However dual topology approaches suffer from a number of technical difficulties which are mainly related to the fact that if a solute does not have any intermolecular interaction with its surroundings, it can drift anywhere in the simulation box. This usually causes the free energy difference to converge very very slowly (in practice not at all). To overcome these difficulties, the dual topology technique implemented in ProtoMS constrains a pair of solutes to stay together by the introduction of dummy bond between the center of geometry of the two solutes. As this does not prove to be sufficient to avoid convergence issues, a soft-core non bonded energy function is also implemented. In essence, the function that computes the intermolecular energy of the solutes is modified such that when a solute is not fully interacting with its surroundings, it’s Lennard-Jones and couloumbic energies are softened such that atomic overlaps do not result in very large, positive, energies. The solute is effectively ‘softer’. There are three soft-core versions implemented in ProtoMS. The original implementation in ProtoMS for a solute that is being turned off is described by equation (17).

(17)![U_{non bonded,\lambda}= (1-\lambda) 4{\epsilon}_{ij} \left[ \left( \frac{ \sigma_{ij}^{12} }{ ( \lambda \delta \sigma_{ij} + r_{ij}^{2} )^{6}} \right) - \left( \frac{ \sigma_{ij}^{6} }{ (\lambda \delta \sigma_{iJ} + r_{ij}^{2})^{3} } \right) \right] + \frac{(1-\lambda)^{n} q_{i}q_{j}} {4\pi{\epsilon}_{0}\sqrt{(\lambda + r_{ij}^{2})}}](_images/math/ec2fe89da7a0949bb709049fc3a00a569841c035.png)

where the parameters n and  control the softness of the Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interactions respectively.

control the softness of the Coulombic and Lennard-Jones interactions respectively.

An alternative that has been useful in some applications is described by equation (18)

(18)![U_{non bonded,\lambda}= (1-\lambda) 4{\epsilon}_{ij} \left[ \left( \frac{ \sigma_{ij}^{12} }{ ( \lambda \delta \sigma_{ij}^6 + r_{ij}^{6} )^{2}} \right) - \left( \frac{ \sigma_{ij}^{6} }{ \lambda \delta \sigma_{iJ}^6 + r_{ij}^{6} } \right) \right] + \frac{(1-\lambda)^{n} q_{i}q_{j}} {4\pi{\epsilon}_{0} \left [ \lambda \delta_c + r_{ij}^{6} \right ]^{1/6}}](_images/math/c59fc713799d25bc91ca757a21b55af1dc210ce8.png)

with an additional softness parameter  for the Coulombic interactions.

for the Coulombic interactions.

Third, the soft-core implementation in the latest version of the Amber package is available and is described by equation (19)

(19)![U_{non bonded,\lambda}= (1-\lambda) 4{\epsilon}_{ij} \left[ \left( \frac{ \sigma_{ij}^{12} }{ ( \lambda \delta \sigma_{ij}^6 + r_{ij}^{6} )^{2}} \right) - \left( \frac{ \sigma_{ij}^{6} }{ \lambda \delta \sigma_{iJ}^6 + r_{ij}^{6} } \right) \right] + \frac{(1-\lambda)^{n} q_{i}q_{j}} {4\pi{\epsilon}_{0} \sqrt{( \lambda \delta_c + r_{ij}^{2})}}](_images/math/4ae27aa331a7b1183de5a564c8cc993bd8c864aa.png)

Generic Moves¶

ProtoMS conducts a simulation by performing a sequence of moves on the system. The following moves are currently implemented

- Residue moves Standard Monte Carlo (MC) moves on protein residues.

- Solute moves Standard MC moves on solute molecules.

- Solvent moves Standard MC moves on solvent molecule.

- Volume moves Monte Carlo moves that change the volume of the system. These are used to run constant pressure simulations.

- GCSolute moves Standard MC moves on GCsolute molecules.

- Insertion moves MC moves which selects a GCsolute with a θ value of 0 and turns it to 1

- Deletion moves MC moves which selects a GCsolute with a θ value of 1 and turns it to 0

- Theta moves MC moves which sample the value of θ on a GCsolute molecule

- Sample moves MC moves which sample the value of θ on a GCsolute molecule whilst applying a biasing potential

-moves Monte Carlo moves that change

-moves Monte Carlo moves that change  . These may be used to perform umbrella sampling free energy simulations.

. These may be used to perform umbrella sampling free energy simulations. - Dual potential moves Works only with implicit solvent simulations. Allows to sample rapidly configurations with a crude potential but correct for errors with a specific acceptance test.

Residue Moves A residue move is a Monte Carlo move on a single protein residue. Obviously, for a residue move to be be performed, at least one protein that has flexible residues must be loaded. Each residue move comprises the following steps

- A protein is picked randomly from the set of proteins that have flexible residues. Note that each protein is weighted equally, so each protein has an equal chance of being chosen, regardless of how many flexible residues it contains. This behaviour is likely to change in future versions of the code, as ideally the probability of choosing to move a protein should be proportional to the number of flexible residues.

- One of the flexible residues within the protein is chosen randomly from the set of all flexible residues in the protein. Again, there is no weighting of residues, so each flexible residue has an even chance of being chosen, despite the size of each residue.

- If the backbone of this residue is flexible, then a random number between 1 and 3 is generated. If the random number is equal to 1, then only a backbone move on the residue will be attempted. If the random number is equal to 2 then only a sidechain move will be attempted, where all of the flexible internals of the residue are moved. If the random number is equal to 3 then a backbone and sidechain move are attempted simultaneously. If the backbone of this residue is fixed, then only a sidechain move is attempted.

- The change in energy that results from this move is evaluated, and then tested according to the Metropolis criterion to decide whether or not to accept the move.

- If the move is accepted, then the new configuration of the residue is saved. If the move was rejected then the original configuration of the residue is restored.

You can change the flexibility of any residue in any protein by using the fixbackbone and fixresidues commands described in section Miscellaneous. All residues of all proteins are flexible by default, and have flexible backbones. You control the maximum amounts that the residue moves via the residue template (see Templates). The actual amount that a residue moves by will be based on random values generated within the limits of the maximum amounts set in the residue template, e.g. if the maximum change of an angle was  , then the angle will be changed by a random value generated evenly between

, then the angle will be changed by a random value generated evenly between  and

and  .

.

Solute Moves A solute move is a Monte Carlo move on a single solute molecule. Obviously, for a solute move to be performed, at least one solute molecule must be loaded. Each solute move comprises the following steps

- A solute is picked randomly from the set of loaded solutes. Each solute is weighted equally, regardless of its size or numbers of degrees of freedom.

- One of the residues is chosen at random within the solute. Again, each residue is weighted equally, regard- less of its size.

- All of the flexible internals of this residue are changed, and the whole solute molecule is randomly translated, and rotated around its center of geometry.

- The change in energy associated with this move is evaluated and then tested via the Metropolis criterion to decide whether or not to accept the move.

- If the move is accepted then the new configuration of the solute is saved. If the move was rejected then the original configuration is restored. You can control the maximum amounts that the solute moves via the solute template (see Templates).

Solvent Moves

A solvent move is a Monte Carlo move on a single solvent molecule. Obviously, for a solvent move to be performed, at least one solvent molecule must be loaded. Each solvent move comprises the following steps

- A solvent molecule is randomly chosen from the set of loaded solvent molecules. If preferential sampling is turned on (see Simulation parameters), then the solvent molecules closest to the preferred solute have a relatively higher weight, so will be more likely to be chosen. If preferential sampling is off, then each solvent is weighted equally, regardless of its relative size or proximity to a solute.

- The solvent molecule is randomly translated and rotated around its center of geometry.

- The change in energy associated with this move is evaluated and used to decide whether or not to accept this move via the Metropolis criterion if preferential sampling was turned off, or via a biased Monte Carlo test if preferential sampling were turned on.

- If the move was accepted then the new solvent configuration is saved, otherwise the original configuration is restored.

You can control the maximum amounts that the solvent is translated and rotated by by editing its solvent template (see Templates).

Volume Moves

A volume move is a Monte Carlo move that changes the volume of the system. This is needed to be able to perform Monte Carlo simulations at constant pressure (i.e. using the NPT ensemble). For a volume move to be performed you need to have loaded a box of solvent molecules, and be running using periodic boundary conditions. A volume move is comprised of the following steps

- A random change in volume is chosen within the range set via the maxvolchange command (see Simulation parameters).

- The volume of the system is changed by this amount by scaling all of the coordinates evenly from the center of the simulation box.

- The change in energy associated with this change in volume is evaluated and used to decide whether or not to accept this move via the constant pressure Monte Carlo test, for the system pressure set via the pressure command (see Simulation parameters).

- If the move is accepted then the new system configuration is saved, otherwise the original system configuration is restored.

GCsolute Moves

A GCsolute move is a Monte Carlo move on a single GCsolute molecule. Each GCsolute move comprises the following steps

- A GCsolute molecule is randomly chosen from the set of loaded GCsolute molecules. The value of

is examined; if it is set to 0 then another is chosen until the examined

is examined; if it is set to 0 then another is chosen until the examined  value is 1. If no GCsolutes with

value is 1. If no GCsolutes with  are available then the GCsolute move is counted as rejected.

are available then the GCsolute move is counted as rejected. - The GCsolute molecule is randomly translated and rotated around its center of geometry. If it attempts to leave the confines of its predefined cubic region then it experiences a huge energetic penalty, ensuring that the Metropolis move is rejected.

- The change in energy associated with this move is evaluated and used to decide whether or not to accept this move via the Metropolis criterion.

- If the move was accepted then the new GCsolute configuration is saved, otherwise the original configuration is restored.

You can control the maximum amounts that the GCsolute is translated and rotated by by editing its template (see Templates). If performing a jaws simulation then a GCsolute is chosen at random in 1. without examining its  value.

value.

Insertion Moves

An insertion move is a Monte Carlo move on a single GCsolute molecule, whereby the  value of a GCsolute is turned from 0 to 1. Each insertion move comprises the following steps;

value of a GCsolute is turned from 0 to 1. Each insertion move comprises the following steps;

- A GCsolute molecule is randomly chosen from the set of loaded GCsolute molecules. The value of

is examined; if it is set to 1 then another is chosen until the examined

is examined; if it is set to 1 then another is chosen until the examined  value is 0

value is 0 - The GCsolute molecule is given a random position and orientation within the GCMC region.

- The value of

for that GCsolute molecule is set to 1, and the new energy associated with this value of

for that GCsolute molecule is set to 1, and the new energy associated with this value of  is calculated

is calculated - The change in energy associated with this move is evaluated and used to decide whether or not to accept this move via the Metropolis criterion.

- If the move was accepted then the new value of

for that GCsolute molecule is saved, otherwise the original value of 0 is restored.

for that GCsolute molecule is saved, otherwise the original value of 0 is restored.

Deletion Moves

A deletion move is a Monte Carlo move on a single GCsolute molecule, whereby the  value of a GCsolute is turned from 1 to 0. Each deletion move comprises the following steps

value of a GCsolute is turned from 1 to 0. Each deletion move comprises the following steps

- A GCsolute molecule is randomly chosen from the set of loaded GCsolute molecules. The value of

is examined; if it is set to 0 then another is chosen until the examined

is examined; if it is set to 0 then another is chosen until the examined  value is 1. If no GCsolutes with

value is 1. If no GCsolutes with  are available then the deletion move is counted as rejected.

are available then the deletion move is counted as rejected. - The value of

for that GCsolute molecule is set to 0, and the new energy associated with this value of

for that GCsolute molecule is set to 0, and the new energy associated with this value of  is calculated

is calculated - The change in energy associated with this move is evaluated and used to decide whether or not to accept this move via the Metropolis criterion.

- If the move was accepted then the new value of

for that GCsolute molecule is saved, otherwise the original value of 1 is restored.

for that GCsolute molecule is saved, otherwise the original value of 1 is restored.

Theta Moves

A theta move is a Monte Carlo move on a single GCsolute molecule, whereby the  value of a GCsolute is sampled. Each theta move comprises the following steps

value of a GCsolute is sampled. Each theta move comprises the following steps

- A GCsolute molecule is randomly chosen from the set of loaded GCsolute molecules

- The value of

for that GCsolute molecule is randomly changed, and the new energy associated with this value of

for that GCsolute molecule is randomly changed, and the new energy associated with this value of  is calculated

is calculated - The change in energy associated with this move is evaluated and used to decide whether or not to accept this move via the Metropolis criterion.

- If the move was accepted then the new value of

for that GCsolute molecule is saved, otherwise the original value of

for that GCsolute molecule is saved, otherwise the original value of  is restored.

is restored.

Sample Moves

A sample move is a Monte Carlo move on a single GCsolute molecule, whereby the  value of a GCsolute is sampled whilst applying a biasing potential, jbias. Each sample move comprises the following steps

value of a GCsolute is sampled whilst applying a biasing potential, jbias. Each sample move comprises the following steps

- A GCsolute molecule is randomly chosen from the set of loaded GCsolute molecules (typically only one GCsolute molecule is studied in a sample move)

- The biasing potential is added onto the value of ieold for that molecule, based upon the volume of the restraint and the applied jbias

- The value of

for that GCsolute molecule is randomly changed, and the new energy associated with this value of

for that GCsolute molecule is randomly changed, and the new energy associated with this value of  is found

is found - The biasing potential is added onto the value of ienew for that molecule, based upon the volume of the restraint and the applied jbias

- The change in energy associated with this move is evaluated and used to decide whether or not to accept this move via the Metropolis criterion.

- If the move was accepted then the new value of

for that GCsolute molecule is saved, otherwise the original value of

for that GCsolute molecule is saved, otherwise the original value of  is restored.

is restored.

Relative Move Probabilities

You can specify which moves should be run by passing arguments to the simulate and equilibrate commands (see Running a Simulation). You can use these commands to assign a weight to each type of move, e.g. 100 for solvent moves, 10 for protein moves, 1 for solute moves and 0 for volume move. The type of move chosen for each step of the simulation is generated randomly based on these set relative weights. These weights mean that on average, in 111 moves, 100 of these moves will be solvent moves, 10 of these moves will be protein moves, 1 of these moves will be solute moves and none of the moves will be volume moves (e.g. no volume moves will be performed). Note that you need to perform some volume moves if you wish to sample from the NPT ensemble!

Executing ProtoMS¶

ProtoMS is a simple program that may be used from the command line. Once you have compiled it you should find it in the top directory (it is called simply protoms3). If you run the program you should see that it prints out some information about the program and license, then it complains that nothing has been loaded so it closes down. The interface to ProtoMS has been designed to allow easy integration of ProtoMS with scripts, and to enable simple use from a command file. A ProtoMS input consists of a set of commands and values, e.g. the command temperature could have the value 25.0 . This would set the simulation temperature to  C. The input is passed to ProtoMS via a command file. The above command could thus be input by setting by placing the line

C. The input is passed to ProtoMS via a command file. The above command could thus be input by setting by placing the line

temperature 25.0

into a file and have ProtoMS read commands from that file. You specify the command file by passing it to ProtoMS on the command line, e.g.

protoms3 mycmdfile.txt

Note that ProtoMS is insensitive to whether commands, variables or contents of files are uppercase or lowercase, so you are free to mix and match capitals and small case wherever you want. The only exception to this is in the specification of filenames, where your operating system may care about case. As an example, depending on your operating system, ProtoMS may fail when the file containing the commands is named in upper case letters.

For replica exchange or ensemble type calculations, you have to execute ProtoMS through an appropriate MPI wrapper, e.g.

mpirun -np 16 protoms3 mycmdfile.txt

File output¶

If you run ProtoMS from the command line you should see that it prints out a lot of information to the screen (on Unix called standard output, STDOUT). If you look closely at the output you should see that each line of output is preceded by a tag, such as ‘HEADER’ or ‘INFO’. ProtoMS uses streams to output data, and these tags state which stream the line of data came from. Thus the information at the top of the output that gives the license and version details has been printed to the ‘HEADER’ stream, while the lines stating that ProtoMS is closing down because nothing has been loaded have gone to the ‘FATAL’ stream. ProtoMS uses the following streams

- HEADER Used to print the program header.

- INFO Used to print general information.

- WARNING Warnings are printed to this stream. ProtoMS will generally try to continue if it detects a problem, and will print out information about any errors to the WARNING stream. It is up to you to check the WARNING stream to ensure that your simulation is working correctly.

- FATAL If an error is so serious that ProtoMS is forced to shutdown then it will first try to tell you what the problem is by sending text to the FATAL stream.

- RESTART The restart file is written to the RESTART stream.

- PDB Any output PDB files are written to the PDB stream.

- MOVE Information about moves are printed to this stream, e.g. whether or not a move was accepted, and how much progress has been made during the simulation.

- ENERGY Information about the energy components for the moves are printed to this stream, e.g. the bond energy of solute 1, or the coulomb energy between protein 1 and the solvent.

- RESULTS The results of the simulation are written to the RESULTS stream. These include the free energy averages and energy component averages.

- DETAIL The DETAIL stream contains lots of additional detail about the setup of the simulation. This can be very verbose, as it includes complete detail of the connectivity of the system and the loaded forcefield. The DETAIL stream is useful when you are setting a simulation up, though should be turned off when you are running production.

- SPENERGY The SPENERGY stream is used to report the results of single point energy calculations.

- ACCEPT The ACCEPT stream is used to print information about the numbers of attempted and accepted moves.

- RETI The RETI stream is used to report the energies needed by the RETI free energy method.

- DEBUG The DEBUG stream is used by the developers to report debugging information during a ProtoMS run. This stream is only active if ‘debug’ is set to true.

These streams may be switched on or off, directed to STDOUT, directed to STDERR or directed to a file. You can do this by using the commands

streamSTREAM STDOUT

streamSTREAM STDERR

streamSTREAM off

streamSTREAM /path/to/file.txt

where STREAM is the name of the stream that you wish to direct (e.g. streamINFO). ProtoMS is insensitive to case, so you could use the command

streaminfo stdout

However, your operating system may be sensitive to case so you should ensure that you use the correct case for filenames.

You are free to direct multiple streams into a single file, or to turn undesired streams off. If a stream is output to STDOUT or STDERR then the name of the stream is prepended to the start of each line. The name is not attached if the stream is directed into a file. The WARNING and FATAL streams are special as unlike the other streams, these two cannot be turned off. These two streams will be directed to STDERR if they have not been directed elsewhere.

By default, the HEADER, INFO, MOVE and RESULTS streams are directed to STDOUT, the WARNING and FATAL streams are directed to STDERR, and the remaining streams are switched off. Bear this in mind if you think that you should be getting output and you are not - make sure that the stream that contains your output is directed to something!

The streamSTREAM command is used to specify the direction of the stream at the start of the simulation. It is possible to redirect streams while the simulation is running. This is slightly more complicated than then streamSTREAM command, and is described in section Miscellaneous.

By default ProtoMS overwrites the files specified by the streamSTREAM command. If you want to append to already existing files, for instance if you are restarting a simulation, you have to add the option

appendstreams on

This option will turn on append mode for all streams, except the RESTART stream that never will be appended.

Simulation parameters¶

There are many commands to set parameters that you can use to control your simulation. To make it easier to search for those relevant to your calculations, these will be divided in several subsections.

In the subsections below, unless otherwise specified:

logicalstands for true or false, yes or no, on or off (depending on your personal preference)integerorintstands for any integer numberfloatstands for any floating point numberstringstands for a string of characters

Parameters for developers¶

debug logical

This turns on or off debugging output that may be useful for ProtoMS developers. By default debug is off.

testenergy logical

This is used to set whether or not to turn on testing of energies. This is useful if you are developing ProtoMS. By default testenergy is off.

General parameters¶

prettyprint logical

Turn on or off pretty printing. With pretty printing turned on, you will see nice starry boxes drawn highlighting certain parts of the output. By default, prettyprint is on.

dryrun logical

Whether or not to perform a dry run of the simulation. If this is true then all of the files will be loaded up and your commands parsed. If there are any problems then these will be reported in the WARNING stream. No actual simulation will be run, though any files that would be created may be created. While this option is very useful for testing your commands, it is not perfect and cannot check everything. I thus recommend that you also perform a short version of your simulation before you commit yourself to full production. By default dryrun is off.

ranseed integer

where integer is any positive integer. This command is used to set the random number seed to be used by the random number generator. The random number seed can be any positive integer, and you will want to specify a seed if you wish to run reproducible simulations. If you do not specify a random number seed then a seed is generated based on the time and date that the simulation started.

temperature float

Use this command to specify the simulation temperature in Celsius. By default temperature is 25.0 C.

pdbparam logical

Whether or not to automatically detect and use, in the simulation, any chunks which might be included in the input PDB files after REMARK. It is most commonly used to include the fixresidues and fixbackbone commands often found at the beginning of a protein scoop. Any chunks included in pdb files will be applied before any other chunk. By default pdbparam is on.

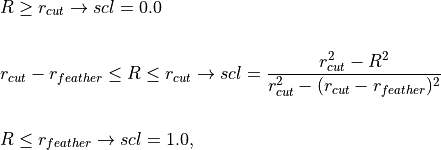

cutoff float

where float is any positive number. This command is used to set the size of the non-bonded cutoff, in Angstroms, used to truncate the intermolecular non-bonded potentials (see eq (1)). By default the non-bonded cutoff is 15A.

feather float

To prevent an abrupt cutoff, the non-bonded energy is scaled quadratically down to zero over the last part of the cutoff (see eq (1)). The feather command sets the distance over which this scaling occurs, e.g.

feather 1.3

sets this feathering to occur over the last 1.3A. The default value of the feather is 0.5A.

cuttype string

where string is either residue or molecule. This specifies the type of non-bonded cutting to use; either residue, where the cutoff is between protein residues, solute molecules and solvent molecules, or molecule, where the cutoff is between protein molecules, solutes molecules and solvent molecules. By default the cuttype is residue.

pressure float

This command sets the pressure of the system in atmospheres. By setting the pressure to a non-zero value you will be able to perform a simulation in the NPT isothermal-isobaric ensemble. Note that you need to perform volume moves (see Generic Moves) to be able to run in the NPT ensemble. By default the pressure is equal to zero, and thus a NPT simulation is not performed.

maxvolchange float

This command sets the maximum change in volume for a volume move in cubic Angstroms. This command only has meaning if an NPT simulation is being performed. By default maxvolchange is equal to the number of solvent molecules divided by ten.

prefsampling integer

This command is used to turn on preferential sampling of the solvent, and to specify which solute is used to define the center of the preferential sampling sphere. The command

prefsampling 1

means that the solvents closest to solute 1 will be moved more frequently than those furthest from solute 1. An optional parameter may be used to change the influence of the sphere, e.g.

prefsampling 1 100.0

will specify a preferential sampling sphere centered on solute 1, with a parameter of 100.0. The larger the parameter, the more highly focused the influence of the sphere around the closest solvent molecules. By default the parameter is 200.0, and preferential sampling is turned off.

boundary none

This turns off any boundary conditions, i.e. the simulation will be performed in vacuum.

boundary periodic dimx dimy dimz

This turns on periodic boundaries, using a orthorhombic box centered on the origin, with dimensions dimx A by dimy A by dimz A. Note that these dimensions may be modified by any loaded solvent file

boundary periodic ox oy oz tx ty tz

This turns on periodic boundaries using an orthorhombic box with the bottom-left-back corner at coordinates (ox , oy , oz) A and the top-right-front corner at (tx , ty , tz) A. Note that these dimensions may be modified by any loaded solvent file.

boundary cap ox oy oz rad k

This turns on solvent cap boundary conditions. Protein and solute molecules will experience no boundary conditions, while solvent molecules will be restrained within a spherical region of radius rad A, centered at coordinates (ox , oy , oz) A. A half-harmonic restraint with force constant k kcal.mol-1.A-2 is added to the solvent energy if it moves outside of this sphere.

boundary solvent

This sets the boundary conditions to whatever is set by the loaded solvent files. If no solvent files are loaded then no boundary conditions are used. This is the default option, and the method of setting boundary conditions via a solvent file is described in section Solvent File

GBSA parameters¶

surface quality 3 probe 1.4

This command will cause surface area calculations to be performed during the simulation. quality can be set to 1,2,3,4 and will result in increasingly precise surface area calculations. For typical simulations, 3 should be fine and 2 will not give a huge error. probe is the radius of the probe and should be set to 1.4 if you want to calculate the solvent accessible surface area of water, but can be set to 0 if you want to calculate the van der waals surface area of a molecule.

born cut 20 threshold 0.005 proteins

This command will enable Generalised Born energy calculations. Thus to run a full GBSA simulation you should use both the surface and born keywords. cut controls the cutoff distance for the computation of the Born radii. If you work with a medium sized protein scoop of circa 100-150 residues, 20 should be fine but you may want a larger value for simulations of large proteins. threshold controls the number of pairwise terms that are not updated when the effective Born radii must be calculated by the Pairwise descreening approximation. The default value 0.005 appear to be a good tradeoff. Increasing it will make the simulation faster but less accurate. proteins activates the rescaling of the Born radii to compensate for systematic errors of the Pairwise Descreening Approximation in large biomolecules. It should be used only when simulating proteins and then its effectiveness has not been yet convincingly demonstrated.

WARNING: These commands are considered to be deprecated. This means that they are not developed any more and have not been tested extensively with newer features. Dump commands are supported with the simulate command and one can do simple MC sampling with GB. However, it is not sure that free energy or the replica-exchange commands work satisfactorily.

Temperature replica-exchange parameters¶

ProtoMS can perform temperature replica-exchange simulations.

temperaturere integer float float float

is the command to set a replica exchange simulation between the different temperatures given as floats, where float is any positive float, and temperatures are given en Celsius. In principle, any desired number of temperature values can be used, and the simulation will require to be runned in as many cores as temperature values are provided. The integer value stands for the frequency at which the exchange between the different temperature values is attempted. Please, note that this value should be a multiple of the frequency of printing output when the dump commands are used (see Frequent output generation). If no exchange is desired, the frequency of exchange can simply be set to the total number of moves of the simulation.

As an example:

temperaturere 20 25.0 30.0 35.0

corresponds to a simulation which will run at three different temperature windows in parallel, and will attempt swaps between the conformations of different temperature windows each 20 moves.

The temperature replica-exchange command can be used in conjunction with the lambdare command, see below, to add temperature ladders to different values of  .

.

solutetempering 25.0 bndang 3 dih 1 lj 3 coul 1 solu 2 prot 2 solv 2

Turns on replica-exchange with solute tempering (REST). It only works if you have specified temperature replica-exchange (see Temperature replica-exchange parameters). In this type of simulation the system is simulated at 25.0 Celsius, or the temperature set with this command, and the temperatures set with the temperaturere command are used to scale the solute energies. The level of scaling for the different energy components can be set with the rest of the options; bndang controls the internal bond-angle energy terms, dih the internal dihedral energy term, lj the internal van der Waals energy, coul the internal Coulomb energy, solu the interaction with other solutes, prot the interaction with the protein and solv the interaction with solvent molecules. Each argument can be either 1, 2 or 3. If the argument is 1, the energy is scaled with  , where

, where  is the effective inverse temperature of the replica (set with the

is the effective inverse temperature of the replica (set with the temperaturere command) and  is the inverse simulation temperature (set with this command). If the argument is 2, the energy is scaled with

is the inverse simulation temperature (set with this command). If the argument is 2, the energy is scaled with  and if the argument 3 the energy is unscaled.

and if the argument 3 the energy is unscaled.

By default ProtoMS will use different random seeds for each replica in a replica exchange simulation. Setting sameseeds to true will prevent this and all replicas will use the random seed provided in the command file. This is primarily available for backwards compatibility:

sameseeds logical

The value of sameseeds is false by default.

Free energy calculation parameters¶

To be able to run a single simulation for a given lambda value, you will need to use the following parameters:

lambda float

where float is a number between 0.0 and 1.0. Specify the value of  . If a single value is given then that is used for

. If a single value is given then that is used for  . If three values are given then these are used for

. If three values are given then these are used for  , and

, and  in the forwards and backwards windows, e.g.

in the forwards and backwards windows, e.g.

lambda 0.5 0.6 0.4

would set  for the reference state to 0.5,

for the reference state to 0.5,  for the forwards perturbed state to 0.6, and

for the forwards perturbed state to 0.6, and  for the backwards perturbed state to 0.4. By default all values of

for the backwards perturbed state to 0.4. By default all values of  are 0.0.

are 0.0.

To run several at several values of  in parallel and hence perform your full perturbation at once with ProtoMS, you will need the commands shown below. Running your free energy calculation in this manner, you will be able to attempt exchanges between the configurations of your system at the different lambdas, increasing the probability of convergence.

in parallel and hence perform your full perturbation at once with ProtoMS, you will need the commands shown below. Running your free energy calculation in this manner, you will be able to attempt exchanges between the configurations of your system at the different lambdas, increasing the probability of convergence.

lambdare integer float float float

is the command to set a replica exchange calculation between the different  given as floats, where

given as floats, where float is a number between 0.0 and 1.0. In principle, any desired number of  values can be used, and the simulation will require to be runned in as many cores as

values can be used, and the simulation will require to be runned in as many cores as  values are provided. The integer value stands for the frequency at which the exchange between the different

values are provided. The integer value stands for the frequency at which the exchange between the different  values is attempted. Please, note that this value should be a multiple of the frequency of printing output when the dump commands are used (see Frequent output generation). If no exchange is desired, the frequency of exchange can simply be set to the total number of moves of the simulation.

values is attempted. Please, note that this value should be a multiple of the frequency of printing output when the dump commands are used (see Frequent output generation). If no exchange is desired, the frequency of exchange can simply be set to the total number of moves of the simulation.

As an example:

lambdare 20 0.000 0.333 0.667 1.000

corresponds to a simulation which will run at four different  windows in parallel, and will attempt swaps between the conformations of different

windows in parallel, and will attempt swaps between the conformations of different  windows each 20 moves.

windows each 20 moves.

With temperature replica-exchange

temperatureladder lambda float float

is one of the commands required to proceed with a simulation including both temperature and  replica exchange, where

replica exchange, where float is each of the  values where a temperature ladder is desired. All

values where a temperature ladder is desired. All  values must be among those included after the

values must be among those included after the lambdare keyword. In principle, the number of temperature ladders can be as high as the number of  windows.

windows.

As an example:

temperatureladder lambda 0.00 1.00

corresponds to a simulation which runs the  windowns 0.00 and 1.00 at all temperatures included after the

windowns 0.00 and 1.00 at all temperatures included after the temperaturere keyword, as far as the corresponding lambdaladder command line is set accordingly.

lambdaladder temperature float float

is one of the commands required to proceed with a simulation including both temperature and  replica exchange, where

replica exchange, where float is each of the temperature values where a  ladder is to be placed. All temperature values must be among those included after the

ladder is to be placed. All temperature values must be among those included after the temperaturere keyword. In principle, the number of lambda ladders can be as high as the number of temperatures in temperaturere. The number of cores must be calculated based on the number of  ladders and temperature ladders, as well as

ladders and temperature ladders, as well as  and temperature values per ladder, taking into account the cores shared by each

and temperature values per ladder, taking into account the cores shared by each  ladder with each temperature ladder.

ladder with each temperature ladder.

As an example:

lambdaladder temperature 25.0 35.0

corresponds to a simulation which runs all  windowns at temperatures 25.0 and 35.0, as far as the corresponding

windowns at temperatures 25.0 and 35.0, as far as the corresponding temperatureladder command line is set accordingly.

All replica-exchange commands together:

lambdare 20 0.000 0.333 0.667 1.000

temperaturere 20 25.0 30.0 35.0

temperatureladder lambda 0.00 1.00

lambdaladder temperature 25.0 35.0

correspond to a simulation where  windows 0.000 0.333 0.667 1.000 are simulated at 25.0 and 35.0 Celsius, while at temperature 30.0, only

windows 0.000 0.333 0.667 1.000 are simulated at 25.0 and 35.0 Celsius, while at temperature 30.0, only  windows 0.000 and 1.000 will be simulated.

windows 0.000 and 1.000 will be simulated.

Other free energy commands

dlambda float

where float is a number between 0.0 and 1.0 (often of the order of 0.001). This command sets the gradient for a free energy calculation. It is required for thermodynamic integration (TI) to be applied on the simulation results.

printfe string

where string should be either off, bar or mbar. Whether to print the free energy estimates required to proceed with BAR or MBAR calculations. Take into account that this estimates will take some time. Your simulations may run faster when this option is set to off (default).

In case dual topology is desired, whether it is for a single or multiple  simulation, the following parameters must be used:

simulation, the following parameters must be used:

dualtopologyint integer1 integer2 synctrans syncrot

This turns on the dual topology method of calculating relative free energies, where int1 is the perturbed solute at  = 0.0 and in2 is the solute at

= 0.0 and in2 is the solute at  = 1.0 . If

= 1.0 . If synctrans is set, the rigid body translations of the two solutes will be synchronised. If syncrot is set, the rigid body rotations of the two solutes will also be synchronised.

softcoreint solute integer

This causes the intermolecular energy of solute integer to be softened. Alternatively, you can write all instead of the solute index and all solutes will have their non bonded energy softened. The softcore is only supported for solutes. May alternatively be used as below.

softcoreint solute integer atoms int1 int2 int3...

The atoms keyword indicates that the interactions of only a subset of atoms within a solute should have their interactions softened. Whilst int1, int2, e.t.c. provide indices specifying atoms based on their ordering within the solute template. In principle, superior numerical convergence can be achieved by applying softcores to only the smallest subset of atoms required to prevent singularities.

softcoreparams coul 1 delta 1.5 gb 0 old

This causes the solutes non bonded energy to be softened with a parameter n set to 1 and  set to 1.5. (see eq (17)). The old keyword selects the original soft-core implementation and can be omitted. If conducting a GBSA simulation, this also causes the GB energy to be softened as well. It is recommended to use the same parameter for the Coulombic and Generalised Born energy. The values listed here, seem to work well for a number of relative binding free energy calculations but actual optimum values of these parameters will depend on your system.

set to 1.5. (see eq (17)). The old keyword selects the original soft-core implementation and can be omitted. If conducting a GBSA simulation, this also causes the GB energy to be softened as well. It is recommended to use the same parameter for the Coulombic and Generalised Born energy. The values listed here, seem to work well for a number of relative binding free energy calculations but actual optimum values of these parameters will depend on your system.

softcoreparams coul 1 delta 0.2 deltacoul 2.0 soft66

This causes the solutes non bonded energy to be softened with a parameter n set to 1,  set to 0.2 and

set to 0.2 and  set to 2.0. (see eq (18)). The soft66 keyword selects the second soft-core implementation, eq (18) .